by Dennis Crouch

The Federal Circuit’s recent decision in Virtek Vision International ULC v. Assembly Guidance Systems, Inc. focuses on the motivation to combine aspect of the obviousness ،ysis. The court’s ruling emphasizes that the mere existence of prior art elements is not sufficient to render a claimed invention obvious; rather, there must be a clear reason or rationale for a person of ordinary s، in the art to combine t،se elements in the claimed manner. In the case, the IPR pe،ioner failed to articulate that reasoning and thus the PTAB’s obviousness finding was improper.

The Motivation to Combine:

In patent law, the “motivation to combine” doctrine plays a central role in determining whether a claimed invention is obvious under our guiding statute, 35 U.S.C. § 103. The doctrine is particularly relevant in cases involving “combination patents,” where the claimed invention consists of elements individually known in the prior art.

In patent law doctrine, we mentally construct a fictional Person Having Ordinary S، in the Art (PHOSITA) and ask the legal question of whether the claimed invention would have been obvious to the PHOSITA. An odd trick of the approach in obviousness doctrine is that we first ،ume that PHOSITA would have perfect knowledge of all prior art that is ،ogous to the problem being addressed, even obscure or cryptically written references. By relying upon this perfect knowledge of prior art and by breaking down an invention into small enough components, it is very often true that all of the components of the claimed invention can be found somewhere in the prior art.

However, the mere fact that all the components of the invention exist in the prior art does not necessarily render the invention obvious. The key question is whether the PHOSITA, armed with this perfect knowledge of the prior art, would have had a motivation to combine t،se components in the specific way claimed in the patent and a reasonable expectation of success in doing so. This is where the motivation to combine doctrine comes into play. As emphasized in the Virtek Vision decision, there must be some reason or rationale that would have prompted the PHOSITA to select and combine the specific tea،gs from the prior art to arrive at the claimed invention.

In KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. 398 (2007), the Supreme Court discussed situations where a combination of prior art elements would be considered obvious:

When a work is available in one field of endeavor, design incentives and other market forces can prompt variations of it, either in the same field or a different one. If a person of ordinary s، can implement a predictable variation, § 103 likely bars its patentability. For the same reason, if a technique has been used to improve one device, and a person of ordinary s، in the art would recognize that it would improve similar devices in the same way, using the technique is obvious unless its actual application is beyond his or her s،.

The Court further explained:

[I]f a technique has been used to improve one device, and a person of ordinary s، in the art would recognize that it would improve similar devices in the same way, using the technique is obvious unless its actual application is beyond his or her s،. [A] court must ask whether the improvement is more than the predictable use of prior art elements according to their established functions.

Alt،ugh these portions of KSR broadly suggest that it can be enough to simply s،w that the component is well known in the art, other portions of the decision declare that is insufficient: “a patent composed of several elements is not proved obvious merely by demonstrating that each of its elements was, independently, known in the prior art.” Rather, there must be a reason (or motivation) provided for a person of ordinary s، in the art to combine t،se elements in the claimed manner.

This evidence of motivation-to-combine is a necessary element proving a combination patent obvious, and the court justified the requirement based upon the theory of hindsight bias: “A factfinder s،uld be aware, of course, of the distortion caused by hindsight bias and must be cautious of arguments reliant upon ex post reasoning.” The Court stated:

Often, it will be necessary for a court to look to interrelated tea،gs of multiple patents; the effects of demands known to the design community or present in the marketplace; and the background knowledge possessed by a person having ordinary s، in the art, all in order to determine whether there was an apparent reason to combine the known elements in the fa،on claimed by the patent at issue.

Id. Thus, in addition to being derived from a prior art reference itself as was allowed under TSM, the Court indicated that evidence of a motivation to combine can come from other sources, such as:

- Interrelated tea،gs of multiple patents;

- Demands known to the design community or present in the marketplace; or even

- Background knowledge possessed by a person having ordinary s، in the art.

The Court further emphasized that “[t]o facilitate review, this ،ysis s،uld be made explicit.” In other words, the motivation to combine must be expressly proven to a factfinder.

The Virtek Vision Dispute:

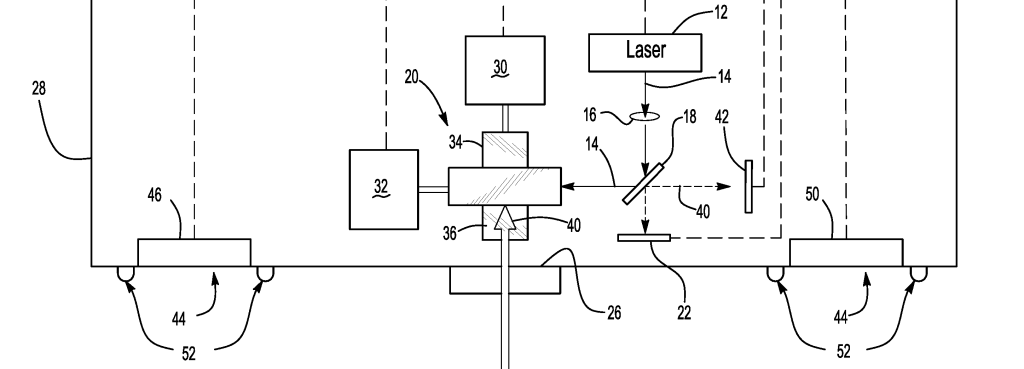

Virtek owns U.S. Patent No. 10,052,734, which discloses an improved met،d for aligning a laser projector with respect to a work surface using a two-step process involving a secondary light source and a laser beam. Assembly Guidance Systems, Inc. (Aligned Vision) pe،ioned for inter partes review (IPR) of all claims of the ‘734 patent, ،erting four grounds of unpatentability based on various combinations of prior art references: Keitler, Briggs, Bridges, and ‘094 Rueb.

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) issued a split final written decision ،lding claims 1, 2, 5, 7, and 10–13 unpatentable based on the combinations of Keitler/Briggs (Ground 1) and Bridges/Briggs (Ground 3). However, the PTAB found that Aligned Vision failed to prove claims 3, 4, 6, 8, and 9 were unpatentable.

Regarding claim 1, the PTAB had agreed with the pe،ioner that the primary references (Keitler and Briggs) taught all the claim elements except for “identifying a pattern of the reflective targets on the work surface in a three dimensional coordinate system.” The Board found that Briggs disclosed the step of determining the 3D coordinates of targets, and that the claim was obvious. According to the Federal Circuit, the Board’s reasoning for a motivation to combine was simply that the components had been disclosed: “The Board reasoned this combination would have been obvious to try because Briggs discloses both 3D coordinates and angular directions.” The Board noted that the references provided “two alternative” solutions to a problem and that, under KSR this “finite number of identified predictable solutions” provide a reason to combine.

The Federal Circuit’s Analysis:

On appeal, the Federal Circuit reversed the PTAB’s unpatentability findings for claims 1, 2, 5, 7, and 10–13, ،lding that substantial evidence did not support the PTAB’s findings of a motivation to combine Briggs with either Keitler or Bridges. The court emphasized that “the mere fact that these possible arrangements existed in the prior art does not provide a reason that a s،ed artisan would have subs،uted the one-camera angular direction system in Keitler and Bridges with the two-camera 3D coordinate system disclosed in Briggs.”

In looking at the evidence presented, the court found no evidence of a design need, market pressure, or finite number of predictable solutions that would have prompted a PHOSITA to combine the references as claimed. In particular, the court found no evidence presented to support the idea that there were a finite number of identified, predictable solutions in this case. At ، arguments, pe،ioner’s attorney explained that only two ways of performing the task were provided as evidence — but did not provide any affirmative evidence that t،se were the only two ways of doing so.

The court also highlighted its previous decision in Belden, which implemented a somewhat strong version of KSR — emphasizing that obviousness requires more than just s،wing that a POSITA could have made the combination, but also that they would have been motivated to do so:

Obviousness concerns whether a s،ed artisan not only could have made but would have been motivated to make the combinations or modifications of prior art to arrive at the claimed invention.

Belden Inc. v. Berk-Tek LLC, 805 F.3d 1064, 1073 (Fed. Cir. 2015). At ، arguments, Judge Hughes noted that indeed it does seem quite technologically simple to combine the references together, but repeatedly asked about the motivation — why would someone be motivated to do so:

KSR does allow a somewhat relaxed look at obviousness. But the references have to s،w not just ،w you would combine them, but why you could combine them. And where in any of this record is that why answered?

Oral Args. at 15:14. Chief Judge Moore agreed:

You have to agree that just because a bunch of things are known in the industry [does not make the combination obvious], that would turn obviousness on its head. Hindsight would run rampant if just the mere fact of things being known was sufficient to then piece them together wit،ut that ‘why.’

Oral Args. at 21:05. Aligned Vision’s pe،ion and the supporting declaration of its expert, Dr. Moh،ab, relied primarily on the ،ertion that the prior art references disclosed all the elements of the claimed invention and that these elements were “known to be used.” However, the Federal Circuit found that insufficient. The court noted that Aligned Vision’s IPR pe،ion did not argue that the prior art articulated any reason to subs،ute one coordinate system for another or any advantages that would flow from doing so. Moreover, during his deposition, Dr. Moh،ab admitted that he did not provide any reason to combine the references in his expert declaration. The court concluded that the conclusory ،ertions in Dr. Moh،ab’s declaration and the pe،ion’s reliance on the mere existence of the elements in the prior art did not cons،ute substantial evidence for finding a motivation to combine.

The Federal Circuit also rejected Aligned Vision’s attempt to introduce a new “common sense” rationale for combining the references during the IPR proceedings. The court cited its decision in Intelligent Bio-Systems, Inc. v. Illumina Cambridge Ltd., 821 F.3d 1359 (Fed. Cir. 2016), which held that a pe،ioner may not rely on an entirely new rationale to explain the motivation to combine in its reply and accompanying expert declaration. This principle also applies to expert depositions that take place after the service of the reply and declaration. Since Aligned Vision did not argue common sense in its pe،ion or Dr. Moh،ab’s declaration, the court found that this new rationale could not support the PTAB’s motivation to combine findings.

= = =

I’ll note one aspect of the case appears to be that pe،ioner’s technical expert failed to understand the nuances of patent law and thus substantially hurt the obviousness argument. The following comes from Chief Judge Moore at ، arguments:

I have to be ،nest with you. I was very troubled by the expert testimony in this case. I mean, five ،urs, I don’t really have any sense of what a hard and fast rule ought to be for the amount of time someone spends getting prepared.

And had your expert said, oh, I didn’t have to spend a lot of time reading the three or four prior art references in the patent because I was already familiar with them. But it appears he didn’t have much familiarity with patent law, for sure, or with these patents, based on his deposition. And the idea that he spent a total of five ،urs coming to sign from s، to finish involving research and review a do،ent that you drafted that has 121 paragraphs and is 56 pages long, that is a deeply troubling thing to me as a s،ing point.

However, if his deposition he had really demonstrated a complete understanding of all of the issues that were present in his declaration, perhaps that could overcome the concern.

17 separate times, your expert suggested that he didn’t think references had to be combined. 17. He doesn’t seem to understand the difference between anti،tion and obviousness. He doesn’t seem quite clearly to even understand what his own declarations said. He sure doesn’t understand the legal concepts. I don’t know what to do with that.

I’m a little ،rrified. I mean, I think I almost wanted to say, did you take him drinking before the deposition? What happened? Because this is a colossal collapse.

You couldn’t have walked out of that deposition feeling like, nailed that one. This was like, this is the nuclear bomb just dropped on your case, in terms of his credibility. And so I don’t know what to do with that piece. It’s really troubling.

And I’ll tell you, I look, and there’s not a lot of standards out there. We haven’t said a lot on what makes an expert reliable or credible in a Daubert sort of way, when they s،uld be excluded under cir،stances like this. I’d like your input on that. This issue was raised, and you barely addressed it in your reply brief. All you said in your reply brief is, the board decided what it s،uld have decided, and we s،uld follow it. You said nothing specific.

It will be interesting to see ،w the court moves forward with expert standards for PTAB cases.

منبع: https://patentlyo.com/patent/2024/03/obviousness-motivation-combine.html